Icy Bodies

Introduction

Icy Bodies is the name of an exhibit at the Exploratorium Created by Shawn Lani.

In the exhibit, small pieces of solid carbon dioxide aka, dry ice, “float” on water and skitter across the surface of the water condensing clouds of water droplets which mark their trail.

The patterns created by these particles are reminiscent of patterns observed in the tails of comets.

Material

A bowl of warm water , at last 25 cm in diameter and at least 1 cm deep.

A dark bowl will provide more contrast .

Dry ice chunks, less than 0.5 cm in diameter.

These can be produced by wrapping larger chunks of dry ice in a towel and then striking them with a hammer

Gloves for handling dry ice

Caution, do not touch the dry ice with your bare hands, frostbite can result after just a few seconds of contact. (Ask me how I know this.)

To Do and Notice

Place some pieces of dry ice in the bowl of water.

Large pieces will sink showing that the density of dry ice, 1.5 g/mL, is greater than the density of water.

Small pieces will float on the surface of the water.

Clouds of white appear around the floating particles.

Jets will propel the particles across the surface of the water leaving behind trails of white cloud. The jets appear as clouds of white.

Jets cause the particles to spin.

Two particles

appear to attract each other when they approach close to each other.

What do you think causes the attraction?

When two particles touch they stick together.

Particles are reflected from the edges of the bowl.

What’s Going On?

Each particle of dry ice is supported by the surface tension of the water. Each particle rests in a smooth depression in the surface of the water created by the gas which sublimes from the particle. If you blow away the cloud from near a particle you can observe this depression in the water surface.

The carbon dioxide sublimes and creates jets of gas which propel the particles across the surface of the water.

When these jets of gas are not directed through the center of mass of the particle they cause the particle to spin.

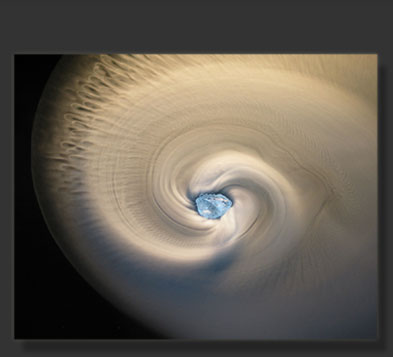

Jets of cold gas race away from the particles creating trails of white clouds condensed from water vapor. If the particle is spinning as these jets are emitted the trails wrap up into spirals.

The clouds ejected from two adjacent particles do not mix. Clouds from two nearby particles are often separated from each other by a thin dark line containing no cloud. This shows how difficult it is to mix air masses.

A particle seems to be attracted to another when it falls into the depression in the surface of the water created by the first particle. Two particles join together at the bottom of their joint bowl. I call this the “valley bed” phenomenon.

Particles are reflected from the edge of the bowl for a similar reason, the water in the bowl is surrounded by a meniscus , a rim of water that rises up the sides of the bowl. Particles collide with this meniscus, ride up the slope and then fall down again reflecting from the edge of the bowl.

So What?

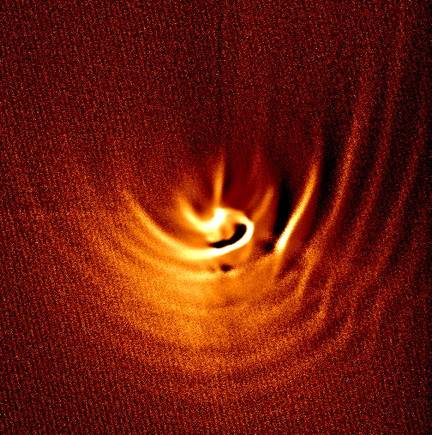

The nucleus of comet Hale-Bopp rotates with a period of approximately 11 hours. As the comet rotates ice rich portions of the comet surface were exposed to sunlight. These places sublimed and shot out jets of gas and dust. These jets spread out in spiral patterns away from the comet. These spirals looked similar to those made by spinning pieces of dry ice.

Spiral shells of gas ejected from comet Hale-Bopp, photo courtesy of the USNO.

Going Further

Charge up a PVC rod by rubbing it with wool. Hold it near one of the stationary pieces of dry ice on the surface of the water. Notice how the dry ice is repelled by the electrically charged rod. What is going on here?

Aluminum coins can be floated on the surface of water using surface tension. It is easiest to float a coin by lowering it onto the water surface using a plastic fork. The coins do not outgas and condense clouds so it is easier to observe the depression in the surface of the water made by the coins, viewed from the side the coins will be seen to be completely below the surface of the surrounding water. It is also easier to explore the attraction of the coins, and the repulsion of the coins by an electrically charged rod than it is the pieces of dry ice.

Paul Doherty

Senior Staff Scientist

The Exploratorium

3601 Lyon St.

San Francisco CA 94123

415-561-0313

pauld@exploratorium.edu